For several centuries before the 1840s Britain had sought to reduce its population by encouraging emigration. Schemes had been devised by many with the hope of riches and settlements established in the Americas. However, it was the successful programme of settlement for some Irish people in Canada in the 1830s which inspired Edward Gibbon Wakefield to propose a system of colonisation based upon what became known as a "vertical slice of society". He planned that those emigrating should include people from all walks of life from the rich to the poor. Wakefield became involved in colonies in South Australia and Canada but it was his drive that was behind the large scale emigration to New Zealand. Some 64 voyages took place carrying overall thousands of people.

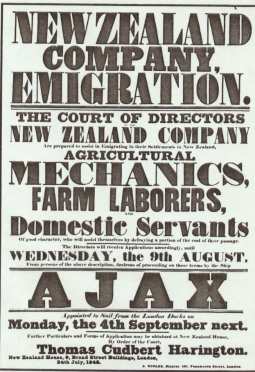

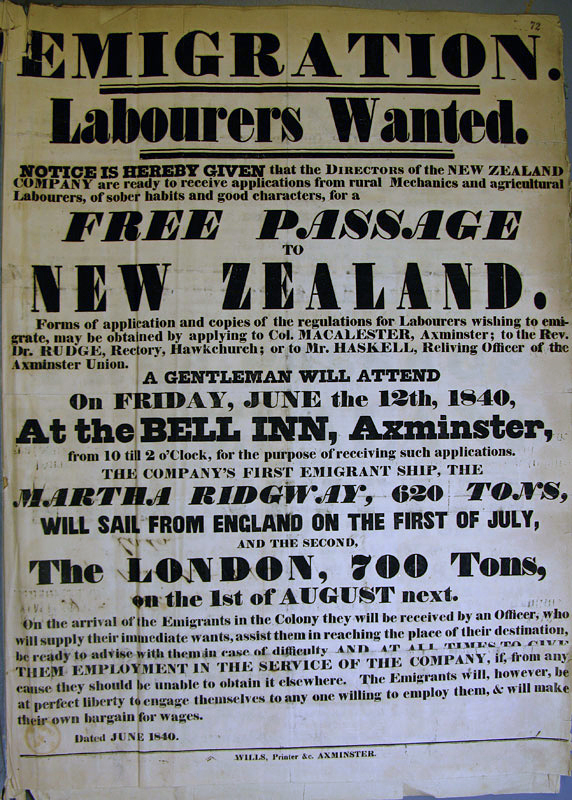

The 1830s were a time when social conditions in England had become very difficult, especially for the poorer people. Riots had broken out as people protested against the Poor Laws. Although Somerset villages, including East Chinnock, do not feature in these disturbances, the chance of a new start in a distant land looked favourable. In the late 1830s and early 1840s the New Zealand Company's agents were in Somerset inviting labourers in particular to take advantage of a FREE PASSAGE to New Zealand. Posters were produced and a Mr Mears interviewed a number of East Chinnock families. Married men with families had to be under forty years of age and single men and women had to be under the age of thirty years. Applicants were advised that a strict enquiry would be made as to their qualifications and character. Land was sold to the more affluent, and professional people had to pay their own way. Unfortunately many did not get to the colony for years and those who arrived early often found that their purchases were not available. Although the successful applicant would have a free passage, money would be needed for eating utensils and for clothing as required by the Company's regulations:

| Males |

Females |

| Six Shirts |

Six Shifts |

| Six Pairs Stockings |

Two Flannel Petticoats |

| Two Pairs Shoes |

Six Pairs Stockings |

| Two Complete Suits |

Two Pairs Shoes |

The East Chinnock Vestry Book records how the Churchwardens and Overseers met to consider how they could assist some poor families to emigrate. An entry for August 1841 states: "the Churchwardens and Overseers were directed to borrow the sum of £50 as a fund for defraying the expenses of the Emigration of Poor Persons having settlements in the said parish". The Poor Law Commissioners ordered that each emigrant may be given clothing to the value of £1 or £2 depending if they were going east or west of the Cape of Good Hope and assistance of at least 3p a mile to help with transport by a local carrier to the port of departure. As was the case of Israel Trask and family, the Montacute carrier was paid £6.15 for conveying them 130 miles to Deptford in September 1841. In July 1841 the persons applying for assistance to go to New Zealand were:

William Pike and family

Luke Harris and family

Joseph Bicknell and family

Nathaniel Bartlett and family

Israel Trask and family

Joseph Rendell and family ( who did not go)

Applying the following year were Joseph Trask and family and John Bartlett and family.

Listed below is a typical entry in the Vestry Book.John Bartlett was 37 years old

Maria, his wife was 34 years old

Joseph, their son was 13 years old

Thomas, their son was 10 years old

Ann, their daughter was 7 years old

Mary, their daughter was 3 years old, and

Robert was three months.

John Bartlett will want to pay for Mary - £3.00

Journey to London - £3.00

Outfit ?

John Bartlett will undertake to pay all expenses if his house and what the Parish allows him will amount to £15. This family are the ancestors of Mr Greg Bartlett. They lived at Badgers Cross. Also in 1842 Thos. Rogers, Eli Young and Matthew Garrett applied to go to Canada, The next year Isaac Churchill and family were granted permission to emigrate to Sydney. In 1844 Thomas Allen and family emigrated to New Zealand; as they were a family of means they paid for their own passage.

Many of the emigrants had a hard time on the somewhat crowded ships. One such was Eli Young, off to Canada, who in his first letter home wrote, "the first three weeks of the passage was bad, the wind against us most of the voyage. June 3 at night a violent gale, it was most desolate. I thought of Robinson Crusoe. I narrowly escaped going to my last and, being short of sailors, we were obliged to go on deck and help while the sailors aloft in the top mast nearly touched the water. I was at the helm with two more men when a great wave came against the vessel and gave her such a turn. It took me from the helm and nearly washed me overboard". On the ships to New Zealand the Company provided a selection of books and in many cases there was schooling available. Likewise the food supplied to the passengers was carefully rationed and was in general adequate. For those going to Canada or to South Australia conditions on arrival were reasonable and they soon settled in. In New Zealand, however, most had a great deal of trouble. Land and work was in most places hard to get. John and Maria Bartlett's family on arrival in Nelson New Zealand were at first accommodated in a large marquee and in time moved as "squatters" into a hut with a clay floor, There was a great deal of difficulty with the Maori inhabitants because of the inept dealings by the New Zealand Company.

Examination of the census returns reveals a curious fact. In spite of the appeal for farm labourers to emigrate and the opportunities given, the Agricultural labourers listed in 1841 were 84 and the 1851 the number had risen to 182, while in 1861 the number was 89. The population figures are:

| 1841 |

Males 337 |

Females 383 |

Total 720 |

| 1851 |

Males 316 |

Females 369 |

Total 685 |

| 1861 |

Males 242 |

Females 310 |

Total 552 |

For a number of years throughout England there had been a steady drift from the countryside into the towns. For East Chinnock this appears to have happened after 1851. Emigration abroad would have continued, though at a slower place, but the lure of work in the towns would have attracted many.

Joseph & Elizabeth Bicknell

Joseph & Elizabeth Bicknell with their children, John age 12, Mary Ann age 7, Sarah age 4, Elizabeth (infant), Harriet age 17 and William age 14 arrived at Port Nicholson (Wellington harbour) New Zealand having left Clifton on February 17th 1842.

Petone (pronounced "pet-own-knee") was the first area of Wellington that was settled starting in about the 1830's. Apparently, the local Maori Chief was getting a little worried by the time the first few ships had arrived, and is reported to have asked if the whole tribe was landing. Petone was subject to a lot of flooding being situated beside the Hutt River mouth. Also there was no provision for a deep water port, so consequently, the area now known as Wellington was established, which provided a much more sheltered and deep water port.

The New Zealand Company was not as “up to speed” as they may have indicated to the early settlers, as there was nothing in the way of cleared land or housing for the settlers, who had quite a time of it, clearing bush and scrub from the land and building accommodation. However, much of this work was done before the Bicknells arrived. Newspapers were already being printed and there was quite a town forming.

Joseph & Elizabeth’s son William is reported to have a Diary farm with 10 cows located about 4-5 miles from the township of Featherston in 1895. A newspaper clipping relating to the death of William's Daughter, Isabel Haycock in August 1952 reports him arriving in the Wairararpa by Bullock wagon. Wairarapa (pronounced why-Ra-rapa) is a Maori word meaning shining or glistening water and relates to the large lake near the township of Featherston, the second largest lake in the North Island.

Elizabeth Bicknell died on the 16th November 1871, and Joseph Bicknell died on the 20th June 1873, both being buried together at Featherston.

Luke Harris and Charlotte Newman

Luke and Charlotte were married in East Chinnock. In the 1841 census they are listed as living there with Luke’s parents, Luke and Anne, who are both aged 70, and their five children. Luke senior and George (Charlotte’s oldest son aged 12 from a previous marriage) are listed as agricultural labourers and Luke is listed as a sail weaver. Luke is aged 25 and Charlotte is 30. In the 1851 UK census there is no mention of any of them and records show that Luke senior died in the Yeovil Workhouse on 21st March 1841. It says he is 81 years old, but it was more likely to be 71. Ann, his wife died in 1864 in East Chinnock. It is unclear why Luke and Ann seemed to have different ends to their lives.

Luke and his family obtained assisted passage under the ‘Poor Scheme’ to New Zealand and on 2nd October 1841, Luke, Charlotte and five children (George aged 12, James aged 9, William aged 6, Sarah Jane aged 4 and Jonah aged 2) and Luke’s brother Charles and his wife Mary, left Gravesend, London on the ‘Clifford’ and arrived in Port Nicholson, Wellington on 15th February 1842. Luke’s sister Elizabeth and her husband William Pike were also assisted under the Poor Scheme.

Luke and Charlotte had more children (Elizabeth, Mary Ann and John) and then we lose track of them.

In 1876 there are local newspaper articles indicating that Luke has abandoned his wife and family, failed to show in court and had a warrant out for his arrest. There are also a number of newspaper clippings around this time where Luke is charged with drunkenness – in April 1876, he is fined 10s or 48 hours prison for his 4th conviction in a month. Two years later in 1878 Luke died at the Empire Stables in Masterton where he was a drover. He was about 62 years old. On his death certificate it was listed as ‘accidental death from an accident’, but there are letters to the editor from Fred Dowsett (Luke’s brother-in-law) in Wellington representing the family, who insisted that it was foul play. Luke is buried in Masterton but there is no headstone.

Charlotte died in 1893, aged 86 and is buried in Karori Cemetery in Wellington. She is in a plot with her daughter, Elizabeth, Elizabeth’s husband Henry Walker, and two of Elizabeth and Henry’s children.

For several centuries before the 1840s Britain had sought to reduce its population by encouraging emigration. Schemes had been devised by many with the hope of riches and settlements established in the Americas. However, it was the successful programme of settlement for some Irish people in Canada in the 1830s which inspired Edward Gibbon Wakefield to propose a system of colonisation based upon what became known as a "vertical slice of society". He planned that those emigrating should include people from all walks of life from the rich to the poor. Wakefield became involved in colonies in South Australia and Canada but it was his drive that was behind the large scale emigration to New Zealand. Some 64 voyages took place carrying overall thousands of people.

The 1830s were a time when social conditions in England had become very difficult, especially for the poorer people. Riots had broken out as people protested against the Poor Laws. Although Somerset villages, including East Chinnock, do not feature in these disturbances, the chance of a new start in a distant land looked favourable. In the late 1830s and early 1840s the New Zealand Company's agents were in Somerset inviting labourers in particular to take advantage of a FREE PASSAGE to New Zealand. Posters were produced and a Mr Mears interviewed a number of East Chinnock families. Married men with families had to be under forty years of age and single men and women had to be under the age of thirty years. Applicants were advised that a strict enquiry would be made as to their qualifications and character. Land was sold to the more affluent, and professional people had to pay their own way. Unfortunately many did not get to the colony for years and those who arrived early often found that their purchases were not available. Although the successful applicant would have a free passage, money would be needed for eating utensils and for clothing as required by the Company's regulations:

| Males |

Females |

| Six Shirts |

Six Shifts |

| Six Pairs Stockings |

Two Flannel Petticoats |

| Two Pairs Shoes |

Six Pairs Stockings |

| Two Complete Suits |

Two Pairs Shoes |

The East Chinnock Vestry Book records how the Churchwardens and Overseers met to consider how they could assist some poor families to emigrate. An entry for August 1841 states: "the Churchwardens and Overseers were directed to borrow the sum of £50 as a fund for defraying the expenses of the Emigration of Poor Persons having settlements in the said parish". The Poor Law Commissioners ordered that each emigrant may be given clothing to the value of £1 or £2 depending if they were going east or west of the Cape of Good Hope and assistance of at least 3p a mile to help with transport by a local carrier to the port of departure. As was the case of Israel Trask and family, the Montacute carrier was paid £6.15 for conveying them 130 miles to Deptford in September 1841. In July 1841 the persons applying for assistance to go to New Zealand were:

William Pike and family

Luke Harris and family

Joseph Bicknell and family

Nathaniel Bartlett and family

Israel Trask and family

Joseph Rendell and family ( who did not go)

Applying the following year were Joseph Trask and family and John Bartlett and family.

Listed below is a typical entry in the Vestry Book.John Bartlett was 37 years old

Maria, his wife was 34 years old

Joseph, their son was 13 years old

Thomas, their son was 10 years old

Ann, their daughter was 7 years old

Mary, their daughter was 3 years old, and

Robert was three months.

John Bartlett will want to pay for Mary - £3.00

Journey to London - £3.00

Outfit ?

John Bartlett will undertake to pay all expenses if his house and what the Parish allows him will amount to £15. This family are the ancestors of Mr Greg Bartlett. They lived at Badgers Cross. Also in 1842 Thos. Rogers, Eli Young and Matthew Garrett applied to go to Canada, The next year Isaac Churchill and family were granted permission to emigrate to Sydney. In 1844 Thomas Allen and family emigrated to New Zealand; as they were a family of means they paid for their own passage.

Many of the emigrants had a hard time on the somewhat crowded ships. One such was Eli Young, off to Canada, who in his first letter home wrote, "the first three weeks of the passage was bad, the wind against us most of the voyage. June 3 at night a violent gale, it was most desolate. I thought of Robinson Crusoe. I narrowly escaped going to my last and, being short of sailors, we were obliged to go on deck and help while the sailors aloft in the top mast nearly touched the water. I was at the helm with two more men when a great wave came against the vessel and gave her such a turn. It took me from the helm and nearly washed me overboard". On the ships to New Zealand the Company provided a selection of books and in many cases there was schooling available. Likewise the food supplied to the passengers was carefully rationed and was in general adequate. For those going to Canada or to South Australia conditions on arrival were reasonable and they soon settled in. In New Zealand, however, most had a great deal of trouble. Land and work was in most places hard to get. John and Maria Bartlett's family on arrival in Nelson New Zealand were at first accommodated in a large marquee and in time moved as "squatters" into a hut with a clay floor, There was a great deal of difficulty with the Maori inhabitants because of the inept dealings by the New Zealand Company.

Examination of the census returns reveals a curious fact. In spite of the appeal for farm labourers to emigrate and the opportunities given, the Agricultural labourers listed in 1841 were 84 and the 1851 the number had risen to 182, while in 1861 the number was 89. The population figures are:

| 1841 |

Males 337 |

Females 383 |

Total 720 |

| 1851 |

Males 316 |

Females 369 |

Total 685 |

| 1861 |

Males 242 |

Females 310 |

Total 552 |

For a number of years throughout England there had been a steady drift from the countryside into the towns. For East Chinnock this appears to have happened after 1851. Emigration abroad would have continued, though at a slower place, but the lure of work in the towns would have attracted many.

Joseph & Elizabeth Bicknell

Joseph & Elizabeth Bicknell with their children, John age 12, Mary Ann age 7, Sarah age 4, Elizabeth (infant), Harriet age 17 and William age 14 arrived at Port Nicholson (Wellington harbour) New Zealand having left Clifton on February 17th 1842.

Petone (pronounced "pet-own-knee") was the first area of Wellington that was settled starting in about the 1830's. Apparently, the local Maori Chief was getting a little worried by the time the first few ships had arrived, and is reported to have asked if the whole tribe was landing. Petone was subject to a lot of flooding being situated beside the Hutt River mouth. Also there was no provision for a deep water port, so consequently, the area now known as Wellington was established, which provided a much more sheltered and deep water port.

The New Zealand Company was not as “up to speed” as they may have indicated to the early settlers, as there was nothing in the way of cleared land or housing for the settlers, who had quite a time of it, clearing bush and scrub from the land and building accommodation. However, much of this work was done before the Bicknells arrived. Newspapers were already being printed and there was quite a town forming.

Joseph & Elizabeth’s son William is reported to have a Diary farm with 10 cows located about 4-5 miles from the township of Featherston in 1895. A newspaper clipping relating to the death of William's Daughter, Isabel Haycock in August 1952 reports him arriving in the Wairararpa by Bullock wagon. Wairarapa (pronounced why-Ra-rapa) is a Maori word meaning shining or glistening water and relates to the large lake near the township of Featherston, the second largest lake in the North Island.

Elizabeth Bicknell died on the 16th November 1871, and Joseph Bicknell died on the 20th June 1873, both being buried together at Featherston.

Luke Harris and Charlotte Newman

Luke and Charlotte were married in East Chinnock. In the 1841 census they are listed as living there with Luke’s parents, Luke and Anne, who are both aged 70, and their five children. Luke senior and George (Charlotte’s oldest son aged 12 from a previous marriage) are listed as agricultural labourers and Luke is listed as a sail weaver. Luke is aged 25 and Charlotte is 30. In the 1851 UK census there is no mention of any of them and records show that Luke senior died in the Yeovil Workhouse on 21st March 1841. It says he is 81 years old, but it was more likely to be 71. Ann, his wife died in 1864 in East Chinnock. It is unclear why Luke and Ann seemed to have different ends to their lives.

Luke and his family obtained assisted passage under the ‘Poor Scheme’ to New Zealand and on 2nd October 1841, Luke, Charlotte and five children (George aged 12, James aged 9, William aged 6, Sarah Jane aged 4 and Jonah aged 2) and Luke’s brother Charles and his wife Mary, left Gravesend, London on the ‘Clifford’ and arrived in Port Nicholson, Wellington on 15th February 1842. Luke’s sister Elizabeth and her husband William Pike were also assisted under the Poor Scheme.

Luke and Charlotte had more children (Elizabeth, Mary Ann and John) and then we lose track of them.

In 1876 there are local newspaper articles indicating that Luke has abandoned his wife and family, failed to show in court and had a warrant out for his arrest. There are also a number of newspaper clippings around this time where Luke is charged with drunkenness – in April 1876, he is fined 10s or 48 hours prison for his 4th conviction in a month. Two years later in 1878 Luke died at the Empire Stables in Masterton where he was a drover. He was about 62 years old. On his death certificate it was listed as ‘accidental death from an accident’, but there are letters to the editor from Fred Dowsett (Luke’s brother-in-law) in Wellington representing the family, who insisted that it was foul play. Luke is buried in Masterton but there is no headstone.

Charlotte died in 1893, aged 86 and is buried in Karori Cemetery in Wellington. She is in a plot with her daughter, Elizabeth, Elizabeth’s husband Henry Walker, and two of Elizabeth and Henry’s children.

East Chinnock

East Chinnock