The Ist July 1916 is justly infamous for being the bloodiest day in the history of the British Army. The British suffered 57,470 casualties (19,240 killed and 2,152 missing, 35,498 men wounded and 580 taken prisoners – from an attacking force of some 120,000 men. By comparison, the French lost 1,590 casualties from a force half the size and the Germans – outnumbered by 7 to 1 – are thought to have lost some 8,000 killed and wounded and 4,200 men taken prisoner.

Although not the worst day of the War (the French lost some 27,000 men killed and 54,000 wounded and prisoners – admittedly in two separate battles – on the 22nd August 1914) it was the nature of the losses that so profoundly affected our memories of the battle, which was an unprecedented experience for the British Army. Seven 'New Army' divisions attacked, alongside three Territorial and four regular Army divisions. The 'New Army' divisions were the Kitchener volunteers of August to November 1914 and were made up in many cases of men from close communities – as were the Territorial units – the idea being that men who were “pals” with each other would perform better as soldiers. The losses meant that many cities and smaller towns had whole streets where each house had lost a father, brother, an uncle or a son. One of the communities to suffer a loss was East Chinnock.

At 7:30 AM on Saturday 1st July, some 66,000 men climbed out of their trenches and attacked the German positions over an 18-mile stretch of ground north of the River Somme in North-Western France. Contrary to the usual image portrayed by the media, they were not all grossly overloaded and they did not all walk slowly and steadily across open ground towards German machine guns. There were 84 battalions (each of some 7-800 men) in the first wave, controlled through a hierarchy of 44 brigade headquarters, 14 divisional headquarters, six Corps headquarters and two Army headquarters. The instructions drawn up by Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Seymour Rawlinson, commanding the British Fourth Army were deliberately vague, to take into account all of the challenges posed to British commanders by the formidable German defences between the Rivers Somme and Ancre. Individual interpretations of these orders down through the chain of command led to many different approaches being used.

The British infantry were supported by the hitherto unprecedented number of 1,437 guns (one for every 17 yards of front line) – 427 of which were “heavy” (i.e., larger than the horse-drawn field guns normally supporting infantry attacks). This was a major effort for the Royal Artillery and several of the East Chinnock men serving in the Artillery would have been present during the week-long bombardment which preceded the attack, during which more than 1.5 million shells were fired, more than during the entire first 12 months of the War:

Driver Herbert Axe (busy in the 29th Division Division’s Ammunition column), and Gunners Maurice Axe, Robert Taylor, Herbert Hallett, Thomas Rendell and Thomas Rockett, all of the Royal Field Artillery, were likely to have been present, while Gunners (and brothers) William, George and John Trask, of the Royal Garrison Artillery, would have been serving the “heavy” guns.

Other East Chinnock men likely to have been involved at some stage were Gilbert Axe of the Royal Army Medical Corps and Driver Harold Taylor and Farrier Sergeant/Acting Staff-Sergeant Albert George Cooper Warr of the Army Service Corps, while Sapper Edward Vagg would have been very busy with the Royal Engineers.

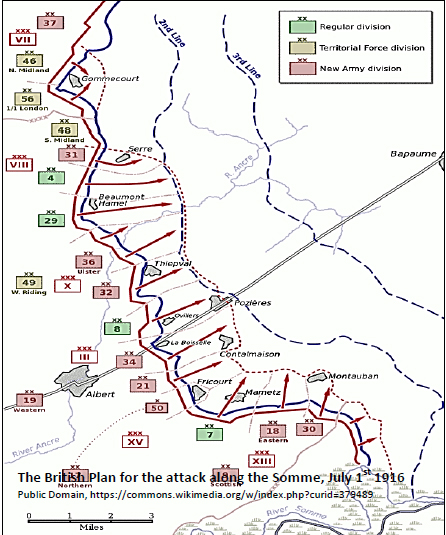

The British Plan for the attack along the Somme, July 1st 1916

Public Domain

The attack can be summed up as complete success in the south, next to the French, by a third of the men involved, disappointing results in the centre by another third – and total failure in the north by the remainder. Sadly for him, Transport Sergeant Walter Pike of 441, Weston St. was one of them. His unit, the 1st Battalion, The Rifle Brigade, was part of the 11th Brigade, 4th Division and was ordered to attack the German positions between the villages of Serre and Beaumont Hamel, both of which had been converted into mini-fortresses by the Germans, who had not been idle in their nearly two years of occupation. Sergeant Pike’s battalion set off at 7:29 AM and soon ran into trouble – the German barbed wire entanglements were uncut by the artillery bombardment and while the men were trying to find a way through, they suffered terribly from the fire of machine guns on either side. The fact that the Rifle Brigade men were exposed to fire from the flanks was due to the complete failure (with 3,600 men killed and wounded – 33% loss rate) of the attack by the 31st Division on Serre, on their left and the corresponding failure of the 29th Division (5,240 casualties, i.e., 50% losses) on their right to make any impression on the strongly-defended positions around Beaumont Hamel.

The complete failure of the first wave was compounded by the arrival of the 11th Brigade’s second wave, including the 1st Battalion, Somerset Light Infantry. These men suffered similarly to their fellows, but small parties managed to penetrate the wire and take part of the German front line trench. They then regrouped and managed to capture most of a position called the Quadrilateral Redoubt. The survivors, now the remnants of six battalions, held off the German counter-attacks with grenades and light machine guns and awaited reinforcement; they were too weak to continue to their planned objective and had quite enough to do to stay where they were. At 9:30 AM the third wave arrived, only to suffer the same fate as the first two; it was not possible to withdraw the men or to reinforce or supply them across the expanse of No Man’s Land that was now completely dominated by German machine-gun and artillery fire. The survivors hung on all afternoon and into the night and were only relieved the next morning. Of the 800-odd men of the 1st Battalion, Somerset Light Infantry, only one warrant officer (Company Sergeant-Major Chappell, of Bath) and 57 unwounded privates answered the roll call. The 4th Division lost 4,692 casualties. The 1st Battalion, The Rifle Brigade lost 59 killed, 248 wounded and 167 missing (killed or prisoner) – a total of 474 casualties out of the 7-800 attacking force. Sergeant Pike is actually listed as having died of wounds on the 2nd July. He was the 30-year-old son of William & Jane Pike of 391 Old Hollows (now “Honeysuckle Cottage”, The Hollow) and was married to Emily. He is remembered at the Doullens Communal Cemetery Extension No. 1.

As for the 1st Battalion, Somerset Light Infantry, every one of the 26 officers was killed (including the commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel J. A. Thicknesse) or wounded and 438 men. Lance-Corporal Walter Axe and Privates Arthur Russ and Alfred Baker of East Chinnock either survived unwounded or were part of the 10% of the battalion’s strength who had been selected to stay out of the battle (a practice that had become universal since the severe casualties suffered by many units during the 1915 attacks – the “reinforcements” providing a core of experienced men around which a battalion could be rebuilt after casualties such as these).

The French attack on the right of the British line was smaller than had been originally intended as troops had had to be diverted to the fighting around Verdun, but their attack went successfully and the preponderance of heavy guns in the French sector also helped the British forces adjacent to them. The French Sixth Army had 552 “heavy” guns and howitzers – allocated to a much shorter 8-mile front - with a much larger supply of high-explosive ammunition for field artillery and far more experienced gunners than the British. Also, it has been calculated that a good third of British shells were faulty and failed to explode; many of these unexploded munitions are still being dug up every day by French farmers, a century later!

Such was the first day of a four-month struggle known as the Battle of the Somme, which was to drag on until winter forced a temporary halt to the fighting in mid-November.

The Ist July 1916 is justly infamous for being the bloodiest day in the history of the British Army. The British suffered 57,470 casualties (19,240 killed and 2,152 missing, 35,498 men wounded and 580 taken prisoners – from an attacking force of some 120,000 men. By comparison, the French lost 1,590 casualties from a force half the size and the Germans – outnumbered by 7 to 1 – are thought to have lost some 8,000 killed and wounded and 4,200 men taken prisoner.

Although not the worst day of the War (the French lost some 27,000 men killed and 54,000 wounded and prisoners – admittedly in two separate battles – on the 22nd August 1914) it was the nature of the losses that so profoundly affected our memories of the battle, which was an unprecedented experience for the British Army. Seven 'New Army' divisions attacked, alongside three Territorial and four regular Army divisions. The 'New Army' divisions were the Kitchener volunteers of August to November 1914 and were made up in many cases of men from close communities – as were the Territorial units – the idea being that men who were “pals” with each other would perform better as soldiers. The losses meant that many cities and smaller towns had whole streets where each house had lost a father, brother, an uncle or a son. One of the communities to suffer a loss was East Chinnock.

At 7:30 AM on Saturday 1st July, some 66,000 men climbed out of their trenches and attacked the German positions over an 18-mile stretch of ground north of the River Somme in North-Western France. Contrary to the usual image portrayed by the media, they were not all grossly overloaded and they did not all walk slowly and steadily across open ground towards German machine guns. There were 84 battalions (each of some 7-800 men) in the first wave, controlled through a hierarchy of 44 brigade headquarters, 14 divisional headquarters, six Corps headquarters and two Army headquarters. The instructions drawn up by Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Seymour Rawlinson, commanding the British Fourth Army were deliberately vague, to take into account all of the challenges posed to British commanders by the formidable German defences between the Rivers Somme and Ancre. Individual interpretations of these orders down through the chain of command led to many different approaches being used.

The British infantry were supported by the hitherto unprecedented number of 1,437 guns (one for every 17 yards of front line) – 427 of which were “heavy” (i.e., larger than the horse-drawn field guns normally supporting infantry attacks). This was a major effort for the Royal Artillery and several of the East Chinnock men serving in the Artillery would have been present during the week-long bombardment which preceded the attack, during which more than 1.5 million shells were fired, more than during the entire first 12 months of the War:

Driver Herbert Axe (busy in the 29th Division Division’s Ammunition column), and Gunners Maurice Axe, Robert Taylor, Herbert Hallett, Thomas Rendell and Thomas Rockett, all of the Royal Field Artillery, were likely to have been present, while Gunners (and brothers) William, George and John Trask, of the Royal Garrison Artillery, would have been serving the “heavy” guns.

Other East Chinnock men likely to have been involved at some stage were Gilbert Axe of the Royal Army Medical Corps and Driver Harold Taylor and Farrier Sergeant/Acting Staff-Sergeant Albert George Cooper Warr of the Army Service Corps, while Sapper Edward Vagg would have been very busy with the Royal Engineers.

The British Plan for the attack along the Somme, July 1st 1916

Public Domain

The attack can be summed up as complete success in the south, next to the French, by a third of the men involved, disappointing results in the centre by another third – and total failure in the north by the remainder. Sadly for him, Transport Sergeant Walter Pike of 441, Weston St. was one of them. His unit, the 1st Battalion, The Rifle Brigade, was part of the 11th Brigade, 4th Division and was ordered to attack the German positions between the villages of Serre and Beaumont Hamel, both of which had been converted into mini-fortresses by the Germans, who had not been idle in their nearly two years of occupation. Sergeant Pike’s battalion set off at 7:29 AM and soon ran into trouble – the German barbed wire entanglements were uncut by the artillery bombardment and while the men were trying to find a way through, they suffered terribly from the fire of machine guns on either side. The fact that the Rifle Brigade men were exposed to fire from the flanks was due to the complete failure (with 3,600 men killed and wounded – 33% loss rate) of the attack by the 31st Division on Serre, on their left and the corresponding failure of the 29th Division (5,240 casualties, i.e., 50% losses) on their right to make any impression on the strongly-defended positions around Beaumont Hamel.

The complete failure of the first wave was compounded by the arrival of the 11th Brigade’s second wave, including the 1st Battalion, Somerset Light Infantry. These men suffered similarly to their fellows, but small parties managed to penetrate the wire and take part of the German front line trench. They then regrouped and managed to capture most of a position called the Quadrilateral Redoubt. The survivors, now the remnants of six battalions, held off the German counter-attacks with grenades and light machine guns and awaited reinforcement; they were too weak to continue to their planned objective and had quite enough to do to stay where they were. At 9:30 AM the third wave arrived, only to suffer the same fate as the first two; it was not possible to withdraw the men or to reinforce or supply them across the expanse of No Man’s Land that was now completely dominated by German machine-gun and artillery fire. The survivors hung on all afternoon and into the night and were only relieved the next morning. Of the 800-odd men of the 1st Battalion, Somerset Light Infantry, only one warrant officer (Company Sergeant-Major Chappell, of Bath) and 57 unwounded privates answered the roll call. The 4th Division lost 4,692 casualties. The 1st Battalion, The Rifle Brigade lost 59 killed, 248 wounded and 167 missing (killed or prisoner) – a total of 474 casualties out of the 7-800 attacking force. Sergeant Pike is actually listed as having died of wounds on the 2nd July. He was the 30-year-old son of William & Jane Pike of 391 Old Hollows (now “Honeysuckle Cottage”, The Hollow) and was married to Emily. He is remembered at the Doullens Communal Cemetery Extension No. 1.

As for the 1st Battalion, Somerset Light Infantry, every one of the 26 officers was killed (including the commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel J. A. Thicknesse) or wounded and 438 men. Lance-Corporal Walter Axe and Privates Arthur Russ and Alfred Baker of East Chinnock either survived unwounded or were part of the 10% of the battalion’s strength who had been selected to stay out of the battle (a practice that had become universal since the severe casualties suffered by many units during the 1915 attacks – the “reinforcements” providing a core of experienced men around which a battalion could be rebuilt after casualties such as these).

The French attack on the right of the British line was smaller than had been originally intended as troops had had to be diverted to the fighting around Verdun, but their attack went successfully and the preponderance of heavy guns in the French sector also helped the British forces adjacent to them. The French Sixth Army had 552 “heavy” guns and howitzers – allocated to a much shorter 8-mile front - with a much larger supply of high-explosive ammunition for field artillery and far more experienced gunners than the British. Also, it has been calculated that a good third of British shells were faulty and failed to explode; many of these unexploded munitions are still being dug up every day by French farmers, a century later!

Such was the first day of a four-month struggle known as the Battle of the Somme, which was to drag on until winter forced a temporary halt to the fighting in mid-November.

East Chinnock

East Chinnock